Transfering files with gRPC

Is transfering files with gRPC a good idea? Or should that be handled by a separate REST API endpoint? In this post, we will implement a file transfer service in both, use Kreya to test those APIs, and finally compare the performance to see which one is better.

Challenges when doing file transfers

When handling large files, it is important to stream the file from one place to another. This might sound obvious, but many developers (accidentally) buffer the whole file in memory, potentially leading to out-of-memory errors. For a web server that provides files for download, a correct implementation would stream the files directly from the file system into the HTTP response.

Another problem with very large files are network failures.

Imagine you are downloading a 10 GB file on a slow connection, but your connection is interrupted for a second after downloading 90% of it.

With REST, this could be solved by sending a HTTP Range header, requesting the rest of the file content without download the first 9 GB again.

For the simplicity of the blogpost and since something similar is possible with gRPC, we are going to ignore this problem.

Transfering files with REST

Handling file transfers with REST (more correctly plain HTTP) is pretty straight forward in most languages and frameworks. In C# or rather ASP.NET Core, an example endpoint offering a file for downloading could look like this:

[HttpGet("api/files/pdf")]

public PhysicalFileResult GetFile()

{

return new PhysicalFileResult("/files/test-file.pdf", "application/pdf");

}

We are effectively telling the framework to stream the file /files/test-file.pdf as the response.

Internally, the framework repeatedly reads a small chunk (usually a few KB) from the file and writes it to the response.

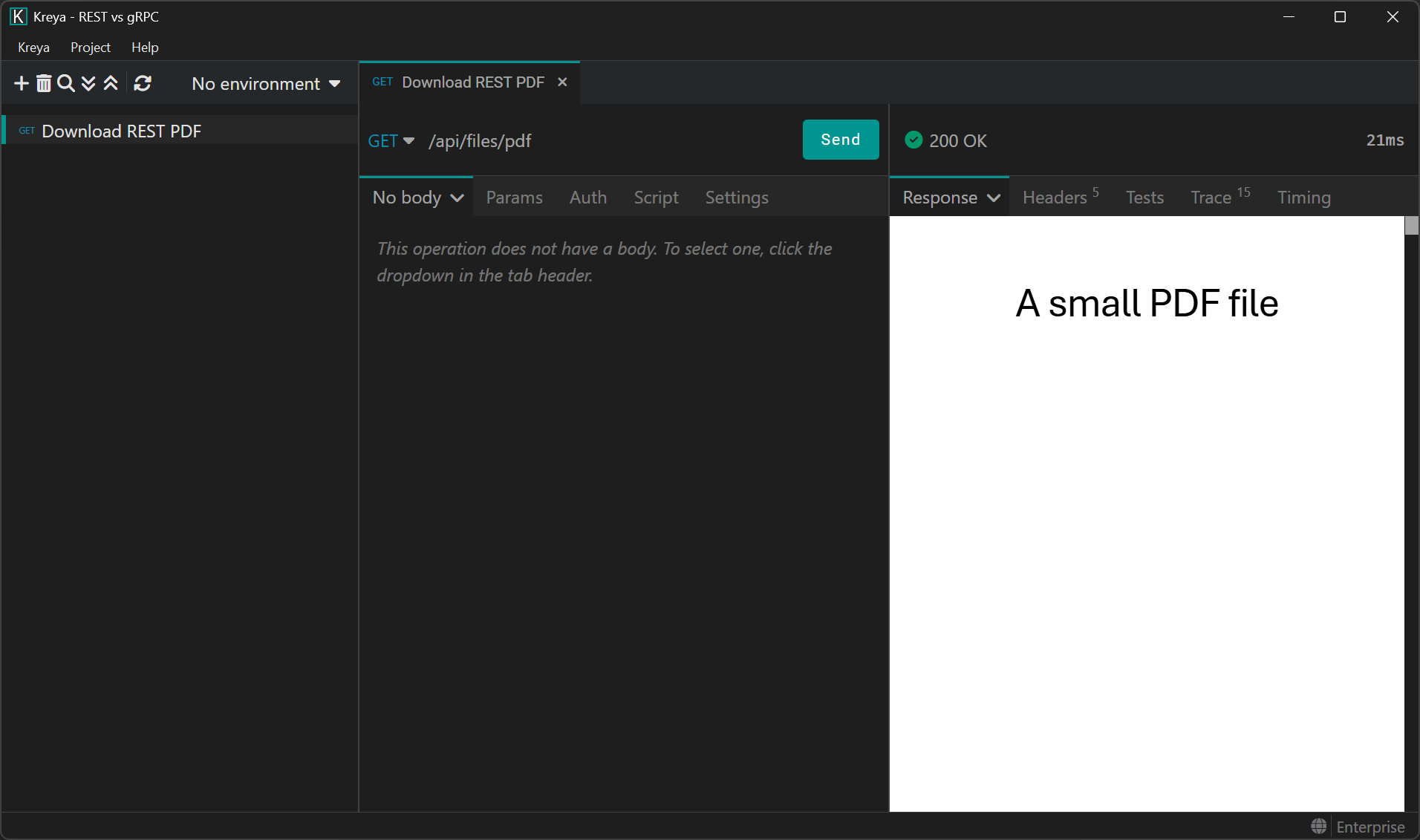

The whole response body will consist of the file content and Kreya, our API client, automatically renders it as a PDF. Other information about the file, such as content type or file name, will have to be sent via HTTP headers.

This is important. If you have a JSON REST API and try to send additional information in the response body like this:

{

"name": "my-file.pdf",

"created": "2026-01-28",

"content": "a3JleWE..."

}

This is bad! The whole file content will be Base64-encoded and takes up 30% more space than the file size itself. In most languages/frameworks (without additional workarounds), this would also buffer the whole file in memory since the Base64-encoding process is usually not streamed while creating the JSON response. If the file itself is also buffered in memory, you could see memory usage over twice the size of the file. This may be fine if your files are only a few KB in size. But even then, if multiple requests are concurrently hitting this endpoint, you may notice quite a lot of memory usage.

Transfering files with gRPC

While the REST implementation was straight forward, this is not the case with gRPC. The design of gRPC is based on protobuf messages. There is no concept of "streaming" the content of a message. Instead, gRPC is designed to buffer a message fully in memory. This is the reason why individual gRPC messages should be kept small. The default maximum size is set at 4 MB. So how do we send large files bigger than that?

While gRPC cannot stream the content of a message, it allows streaming multiple messages. The solution is to break up the file into small chunks (usually around 32 KB) and then send these chunks until the file is transferred completely. The protobuf definition for a file download service could look like this:

edition = "2023";

package filetransfer;

import "google/protobuf/empty.proto";

service FileService {

rpc DownloadFile(google.protobuf.Empty) returns (stream FileDownloadResponse);

}

message FileDownloadResponse {

oneof data {

FileMetadata metadata = 1;

bytes chunk = 2;

}

}

message FileMetadata {

string file_name = 1;

string content_type = 2;

int64 size = 3;

}

This defines the FileService.DownloadFile server-streaming method, which means that the method accepts a single (empty) request and returns multiple responses.

While we could send the file metadata via gRPC metadata (=HTTP headers or trailers), I think it's nicer to define it explicitly via a message.

The server should send the metadata first, as it contains important information, such as the file size.

A naive server implementation in C# could look like this:

private const int ChunkSize = 32 * 1024;

public override async Task DownloadFile(Empty request, IServerStreamWriter<FileDownloadResponse> responseStream, ServerCallContext context)

{

await using var fileStream = File.OpenRead("/files/test-file.pdf");

// Send the metadata first

await responseStream.WriteAsync(new FileDownloadResponse

{

Metadata = new FileMetadata

{

ContentType = "application/pdf",

FileName = "test-file.pdf",

Size = fileStream.Length,

}

});

// Then, chunk the file and send each chunk until everything has been sent

var buffer = new byte[ChunkSize];

int read;

while ((read = await fileStream.ReadAsync(buffer)) > 0)

{

await responseStream.WriteAsync(new FileDownloadResponse

{

Chunk = ByteString.CopyFrom(buffer, 0, read),

});

}

}

This works, but has some issues:

- A new byte array buffer is created for each request

- The buffer is copied each time to create a

ByteString

The first point is easily solved by using a buffer from the shared pool, potentially re-using the same buffer for subsequent requests.

The second point happens due to the gRPC implementation in practically all languages. Since the implementation wants to guarantee that the bytes are not modified while sending them, it performs a copy first. This is a design decision which favors stability over performance. Luckily, there is a workaround by using a "unsafe" method, which is perfectly safe in our scenario and improves performance:

private const int ChunkSize = 32 * 1024;

public override async Task DownloadFile(Empty request, IServerStreamWriter<FileDownloadResponse> responseStream, ServerCallContext context)

{

await using var fileStream = File.OpenRead("/files/test-file.pdf");

// Send the metadata first

await responseStream.WriteAsync(new FileDownloadResponse

{

Metadata = new FileMetadata

{

ContentType = "application/pdf",

FileName = "test-file.pdf",

Size = fileStream.Length,

}

});

// Then, chunk the file and send each chunk until everything has been sent

using var rentedBuffer = MemoryPool<byte>.Shared.Rent(ChunkSize);

var buffer = rentedBuffer.Memory;

int read;

while ((read = await fileStream.ReadAsync(buffer)) > 0)

{

await responseStream.WriteAsync(new FileDownloadResponse

{

Chunk = UnsafeByteOperations.UnsafeWrap(buffer[..read]),

});

}

}

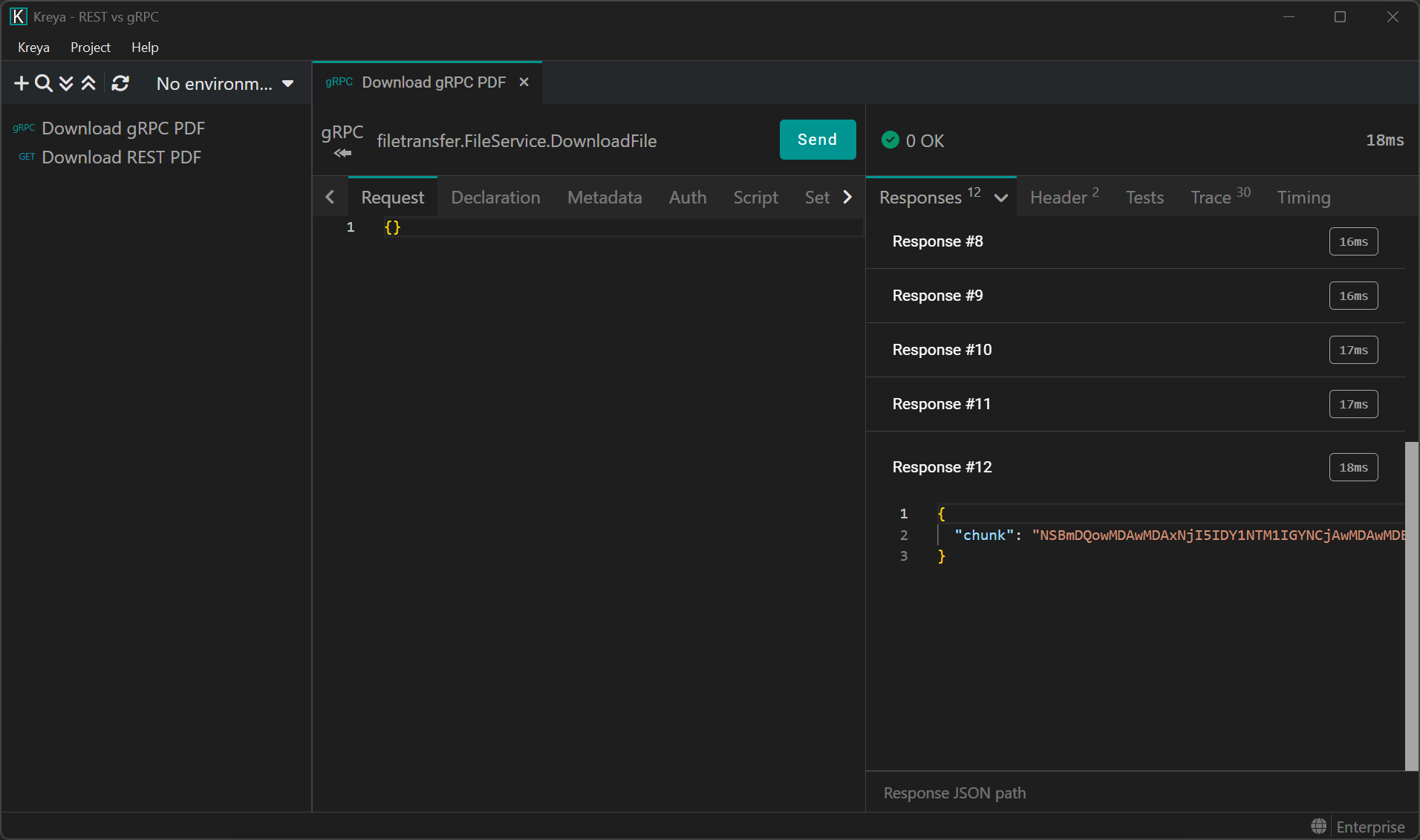

Let's try this out. After importing the protobuf definition, we call the gRPC method with Kreya:

This works, but where is our PDF? Since we are sending individual chunks, we need to put them back together manually.

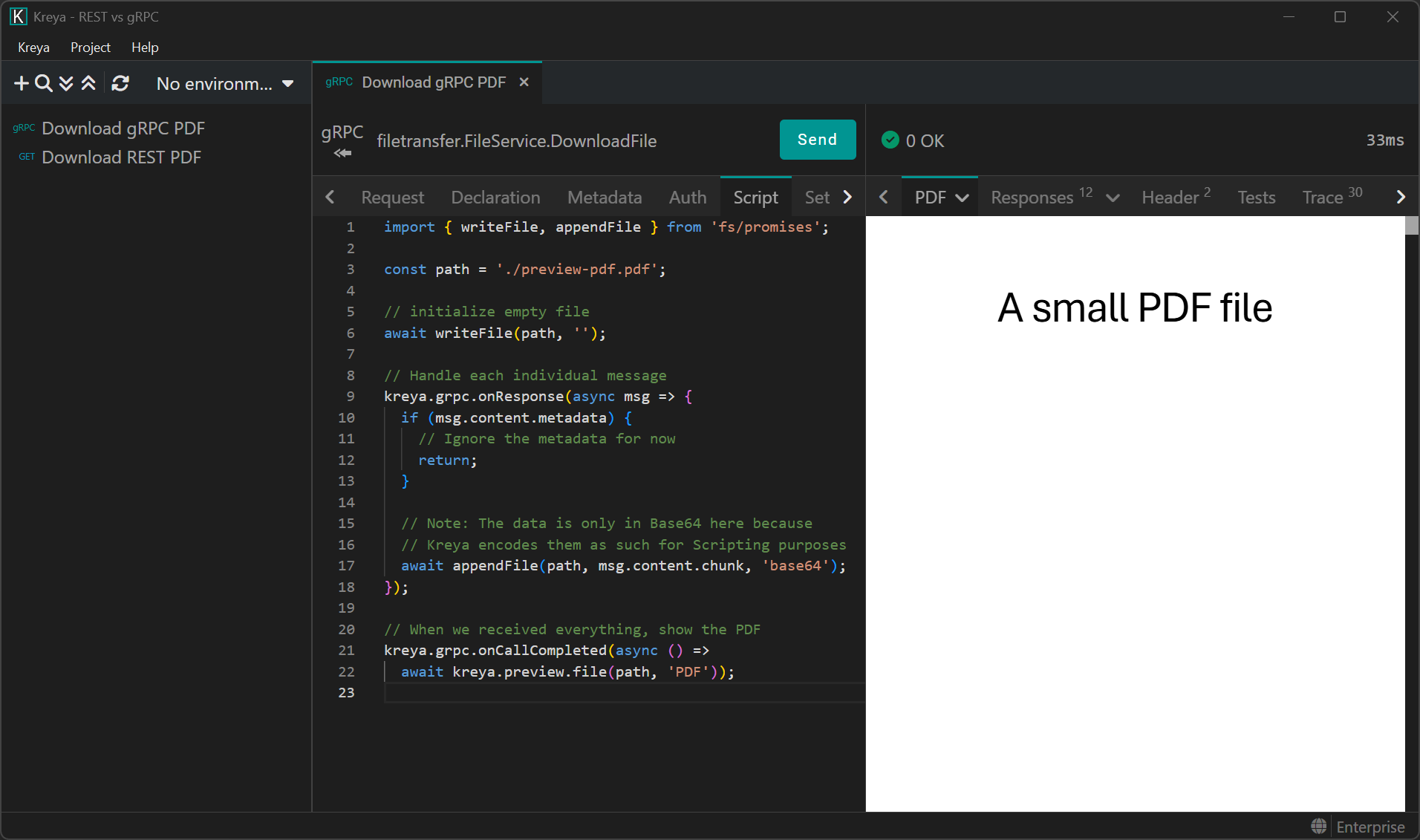

To achieve this, we simply need to append each chunk to a file. In Kreya, this is done via Scripting:

import { writeFile, appendFile } from 'fs/promises';

const path = './preview-pdf.pdf';

// Initialize an empty file

await writeFile(path, '');

// Hook to handle each individual gRPC message

kreya.grpc.onResponse(async msg => {

if (msg.content.metadata) {

// Ignore the metadata for now

return;

}

// Note: The data is only in Base64 here because Kreya encodes them as such for Scripting purposes.

// On the network, gRPC transfers the chunk as length-delimeted bytes

await appendFile(path, msg.content.chunk, 'base64');

});

// When we received everything, show the PDF

kreya.grpc.onCallCompleted(async () => await kreya.preview.file(path, 'PDF'));

This allows us to view the PDF:

Comparison

Great! So transfering files with gRPC is definitely possible. But how do these two technologies compare against each other? Which one is faster and has less overhead?

Total bytes transferred

The total amount of bytes transferred on the wire is actually a pretty difficult topic. It depends on a lot of factors, such as the HTTP protocol (HTTP/1.1, HTTP/2 or HTTP/3), the package size of TCP/IP, whether TLS is being used etc. We are going to take a look how this applies to REST and gRPC.

Streaming files over a gRPC connection generates overhead, although not much. Since gRPC uses HTTP/2 under the hood, each individual chunk message has a few bytes overhead due to the HTTP/2 DATA frame information needed. Additionally, each chunk needs a few bytes to describe the content of the gRPC message. You are looking at roughly 15 bytes per message chunk if it fits into one HTTP/2 DATA frame. Transfering 4 GB of data with a chunk size of 16 KB would need around 250,000 messages to transfer the file completely, incurring an overhead of ~3.7 MB. This may or may not be negilible depending on the use case.

Up- or downloading huge files with REST over HTTP/1.1 has less overhead. Since the bytes of the file are sent as the response/request body, there is not much else that takes up space. In case of uploads to a server, HTTP multipart requests incur a small overhead cost to define the multipart boundary. Additionally, HTTP headers and everything else that is needed to send the request over the wire take up space, but this is the case for all HTTP-based protocols. Downloading files, whether small or large, have roughly the same amount of bytes overhead with HTTP/1.1. Depending on the count and size of HTTP headers, this is around a few hundred bytes.

Funnily enough, transfering files with REST over HTTP/2 incurs a bigger overhead. HTTP/2 splits the payload into individual DATA frames, very similar to our custom gRPC solution. Each frame, often with a maximum size of 16 KB, has an overhead of 9 bytes. For a file 4 GB in size, this amounts to ~2.2 MB overhead. While HTTP/2 has many performance advantages, transfering a single, large file over HTTP/1.1 has less overhead.

In these examples, we omitted the overhead created by TCP/IP, TLS and the lower network layers, which both HTTP/1.1 and HTTP/2 share. Comparing it with HTTP/3, which uses UDP, would make everything even more complicated, so we leave this as exercise for the reader :)

Performance and memory usage

I spun up the local server plus client and took a look at the CPU and memory usage. Please note that this is not an accurate benchmark, which would require a more complex setup. Nevertheless, it provides some insight into the differences between the approaches. The example file used was 4 GB in size.

| gRPC (naive) | gRPC (optimized) | REST (HTTP/1.1) | REST (HTTP/2) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Duration | 24s | 22s | 20s | 28s |

| Max memory usage | 36 MB | 35 MB | 32 MB | 35 MB |

| Total memory allocation | 4465 MB | 165 MB | 38 MB | 137 MB |

If done right, memory usage is no problem for streaming very large files.

And as expected, the naive gRPC implementation which copies a lot of ByteStrings around allocates a lot of memory!

It needs constant garbage collections to clean up the mess.

The maximum memory usage however stays low for all approaches.

What really surprised me was the bad performance of HTTP/2 in comparison to HTTP/1.1. It was even slower than gRPC, which builds on top of it! I cannot really explain this huge difference, especially since the code is exactly the same, both on the client and the server. I was running these tests on .NET 10 on Windows 11.

The optimized gRPC version performs pretty well, but is still slower than REST via HTTP/1.1. Since it has to do more work, it takes longer and uses more memory (and CPU). Optimizing the gRPC code was very important, as the naive implementation allocates so much memory!

I also tested HTTP/1.1 with TLS disabled, but it did not really make a difference.

Conclusion

A REST endpoint for up- and downloading files is still the best option. If you are forced to use gRPC or simply too lazy to add REST endpoints in addition to your gRPC services, transfering files via gRPC is not too bad!

If you use some kind of S3 compatible storage backend, the best options is to generate a presigned URL. Then, download your files directly from the S3 storage instead of piping it through your backend.

There are lots of points to consider when implementing file transfer APIs. For example, if your users may have slow networks, it may be useful to compress the data before sending it over the wire.

Should you need resumable up- or downloads, instead of rolling your own, you could use https://tus.io/. This open-source protocol has implementations in various languages.